Voices from the Archive: Foodstagramming from the E.O. Hoppé Estate Collection

As part of our efforts to share behind-the-scenes looks at some of our projects, we’re thrilled to inaugurate, “Voices from the Archive,” a new series delving into the world of preservation, conservation, cataloguing, digitization, research and importance of our artist and estate collections.

The most extensive collection maintained by Curatorial Advisory is the E.O. Hoppé Estate Collection which contains tens of thousands of negatives, vintage prints, documents and ephemera produced by the German-born, London-based photographer, Emil Otto Hoppé. Considered one of the most important photographers of the Modern era, Hoppé’s artistic versatility is a treasure trove for our archivist team to investigate.

Under the supervision of head archivist, Mark Melville, and art collections manager, Natalia Delgado, the E.O. Hoppé Estate Collection intern team is trained in current museum-standard preservation practices for negatives, prints and digital images as well as art database management. In addition to the general storage and cataloguing of collection assets, our interns pursue important research that is recorded in our custom digital asset management database and published in collection catalogues.

In the spirit of Thanksgiving (for our American friends) and the upcoming holiday season, we’ve selected a story from the E.O. Hoppé Estate Collection to spark some ideas for your holiday cooking…provided it centers around fine dining from nearly a hundred years ago!

A Glimpse Into London’s Culinary History with E.O. Hoppé

by Kathleen Cape

Sifting through the archive of photographer E.O. Hoppé (1878–1972), housed at Curatorial’s offices in Pasadena, I was intrigued to discover a handful of culinary “portraits” (fig. 1–3) hidden among the studio portraits that the archive team and I were in the process of re-housing. As an avid baker and vintage recipe collector, I was immediately taken by these images. Why were these taken and what insight could they provide into the culinary imagination of 1920s London?

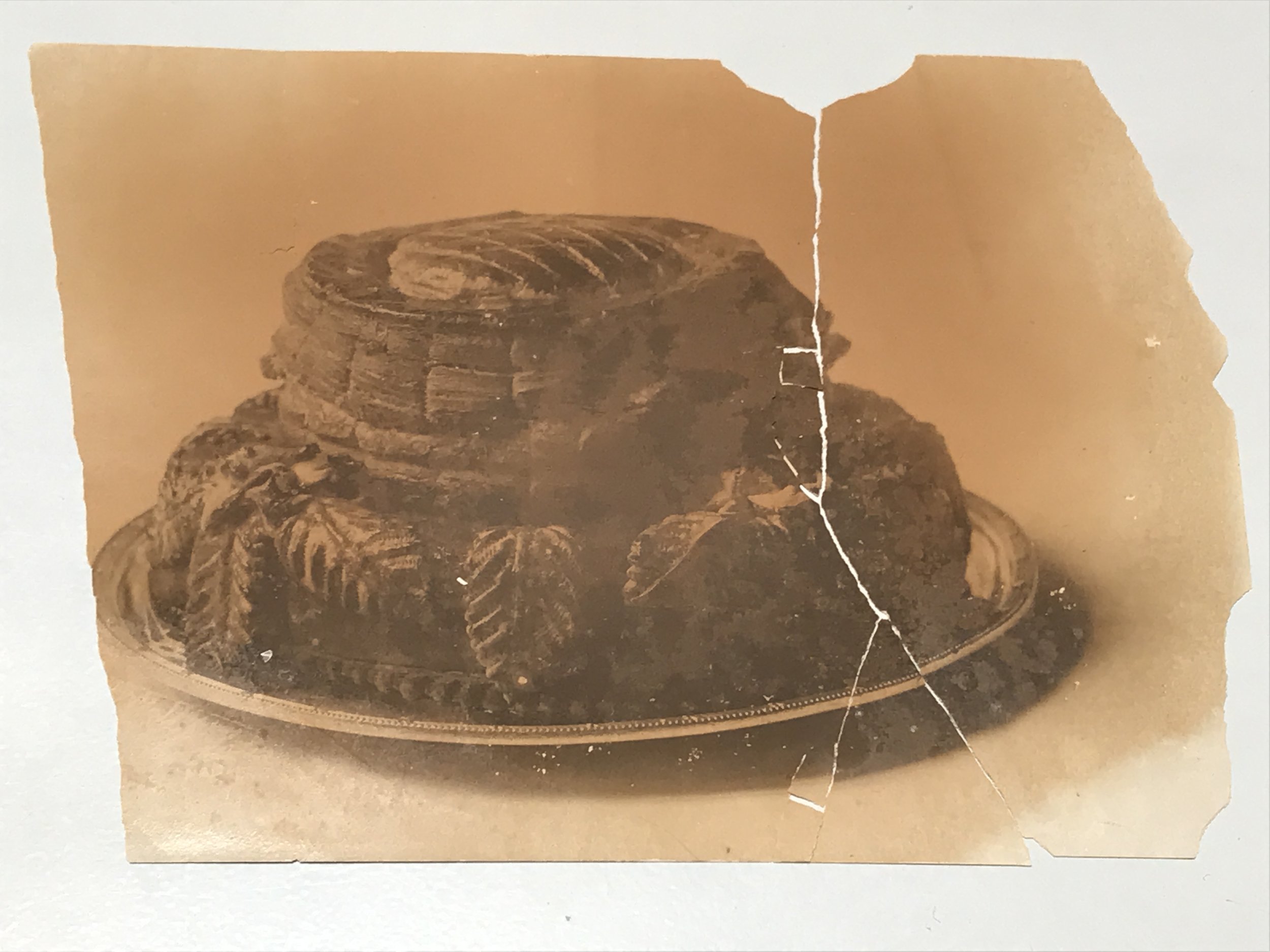

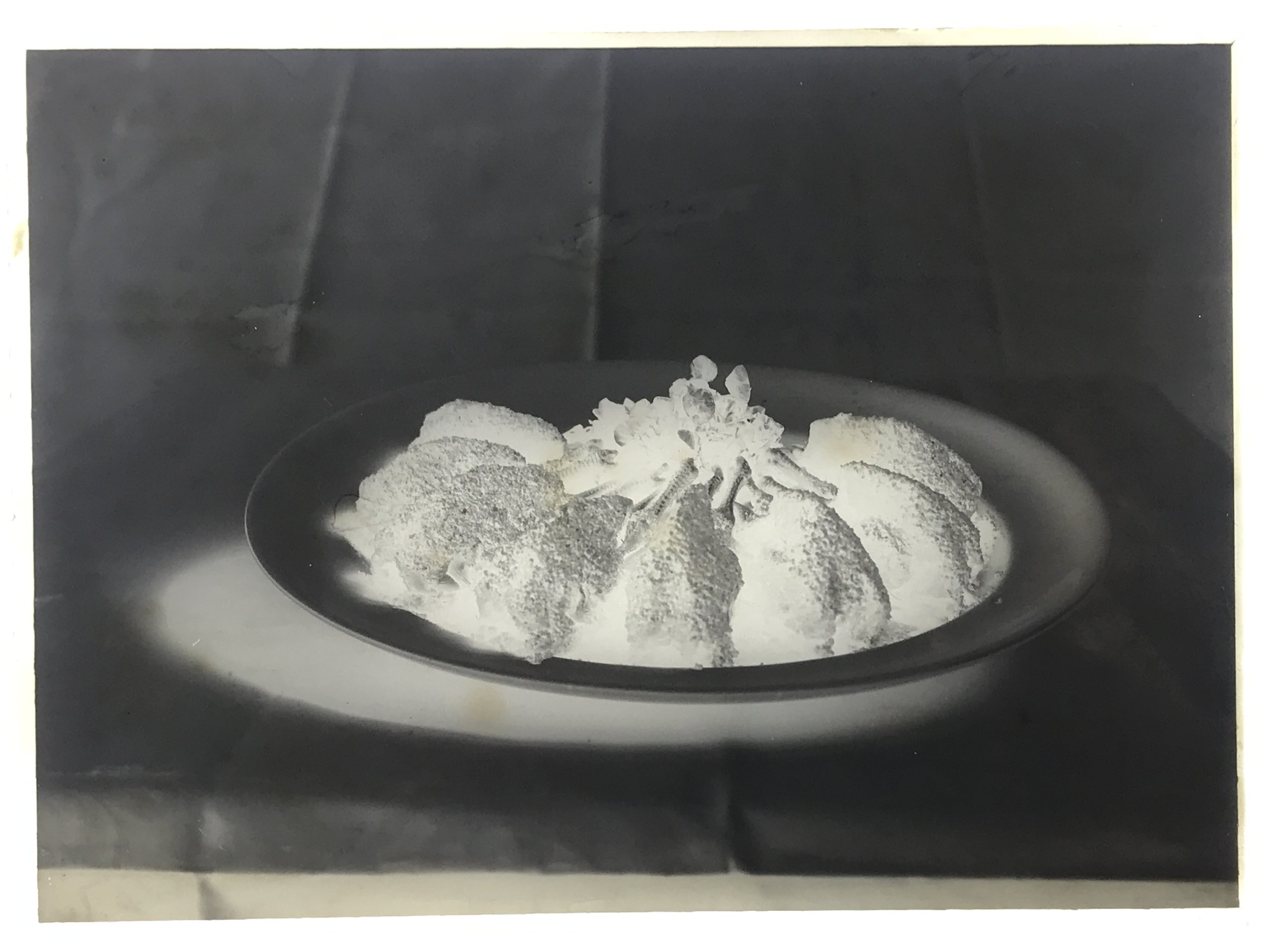

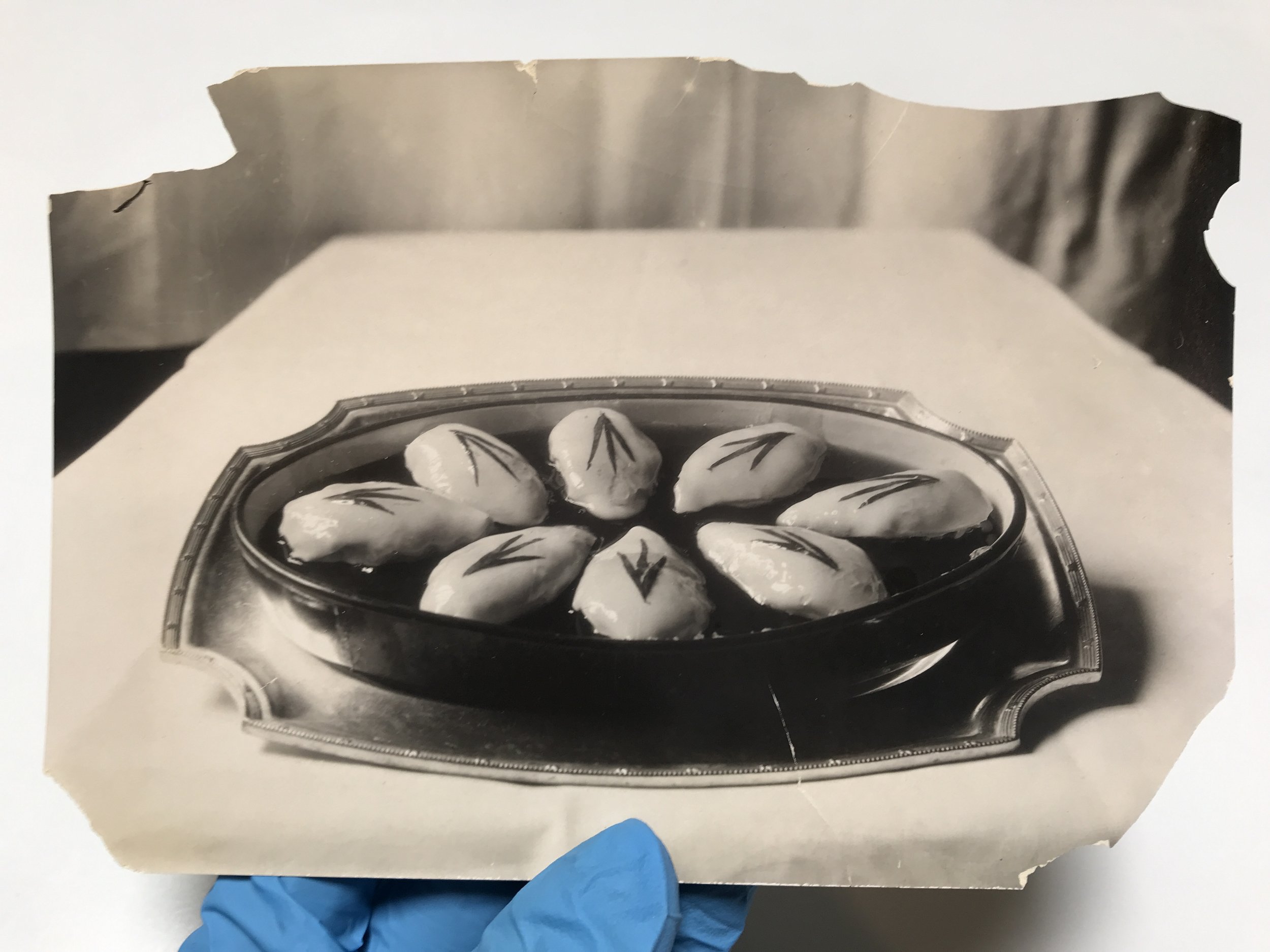

The first culinary negative that caught my eye was the evocatively-named vol-au-vent (literally “flight in the wind,” fig. 1, 4), a delicate, baked puff pastry typically served with a savory filling. The other initial discoveries were glass plates (and contact prints) of the Poussins (“young chickens,” fig. 2, 5) and the selle d’agneau (“saddle of lamb,” fig. 3,6), two finely garnished meat dishes indicative of a rich and decadent dinner out. Quite the series of impressive-looking dishes!

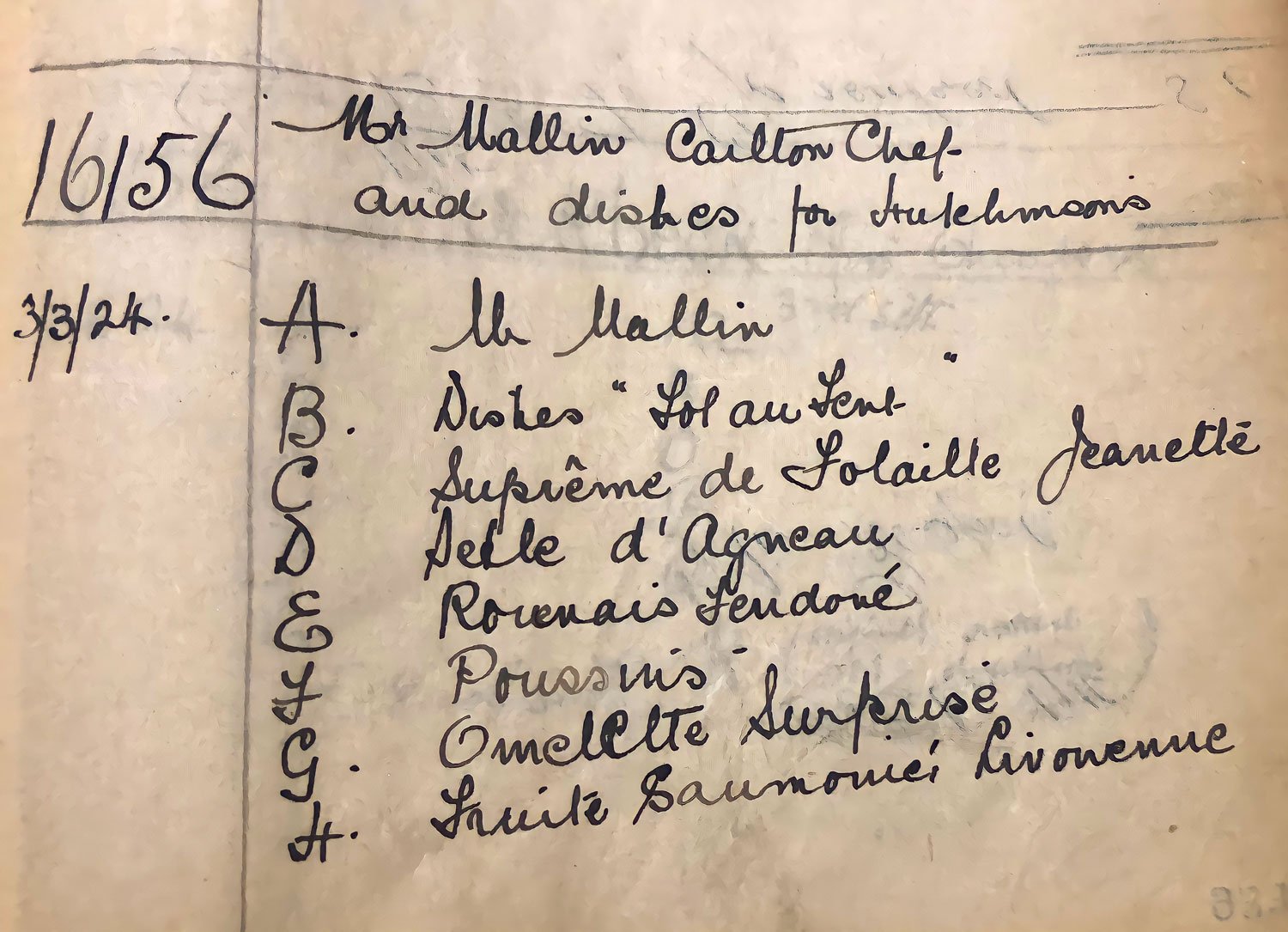

I looked up the inventory numbers in Hoppé’s logbook where I found his hand-written entry: “Mr. Mallin Carlton Chef and dishes for Hutchinson’s”, dated March 3, 1924 (fig. 7). The entry listed three additional dishes, Suprême de volaille Jeanette (“Jeannette chicken supreme”), Omelette surprise, and Truite Saumonée Livonienne (“Livonian salmon trout”) as well as a “Mr. Mallin,” the only human sitter for the session. I eventually located the portrait of Mr. Mallin, (fig. 8–9), who is described in the logbook as a “Carlton chef,” likely referring to The Carlton Hotel and Restaurant (in operation from 1899-1940), which stood at the corner of Haymarket and Pall Mall in London. [1] The Carlton was managed by César Ritz with Auguste Escoffier as the chef de cuisine, and in its early days the hotel and restaurant rivaled The Savoy (also previously managed by Ritz and Escoffier). [2] Lending support to my theory was Escoffier’s Le Guide Culinaire (1903), in which I found nearly every recipe listed in Hoppé’s logbook. [3]

Excitingly, after conferring with the lead archivist and other team members, I was able to track down one more contact print from the series. This print featured the previously-noted Suprême de volaille Jeannette (fig. 11), a complicated recipe with a chaud-froid sauce (and according to one source, named after the ill-fated Jeannette Arctic expedition from 1879–1881). [4] In the words of Escoffier himself: “This method of serving cold entrees, which I inaugurated at the Savoy Hotel with the ‘Suprême de volaille Jeanette,’ is the only one which allows of serving jelly in a state of absolute perfection.” [5]

In addition to Mr. Mallin and his post at The Carlton restaurant, I looked into the mention of “Hutchinson’s”. While Hutchinson was a London-based publisher of books and magazines of the time (now an imprint under Penguin Random House [6]), the name is also a possible reference to Hutchinson’s Magazine. Sadly, I wasn’t able to find the article or book where these photographs were published, but the images do provide some clues as to their purpose. In all four images, the dish itself takes center stage: there are no additional props, and the serving platters are carefully laid out on a simple tablecloth. If Mr. Mallin was indeed a chef at The Carlton, then one possibility is that these images were advertisement or publicity-type photos, meant to entice people to The Carlton’s restaurant. Hoppé took the photos in 1924, well after Ritz had sold his interests in The Carlton Company in 1908, [7] and a few years after Escoffier had retired in 1920. [8] Perhaps The Carlton was experiencing a decline, and was hoping to find new patrons?

In terms of the actual recipes themselves, the six dishes photographed showcase an interest in French grand creations, meant to be admired and consumed in a public setting. Escoffier’s recipe for Omelette en Surprise Néron, for example, calls for the flambéed dessert to be delivered to the dining table still aflame, suggesting the showmanship involved in the presentation of these dishes. [9] Both the tiered vol-au-vent with its decorative leaf motif and the selle d’agneau with its extensive garnish further exemplify the importance placed on presentation, not to mention the impressive size of these dishes.

The staging and apparent marketing of this extravagant food expresses London society’s continued interest in French cuisine. In the early nineteenth century, many French chefs and cooks immigrated to England after the disbanding of aristocratic households caused by the French Revolution [10]. As London high-society grew, social rituals of the elite became more theatrical, and the public consumption of these elaborate meals provided a way for families to display their status and differentiate themselves from the middle class. [11] The conception of French haute cuisine as the cuisine for elite dining endured well into the mid-twentieth century [12], a phenomenon Hoppé evidently held witness to while photographing London’s social elite.

For those looking to try their hand at la grande cuisine, or who wish to learn more about these recipes, I would recommend getting your hands on a copy of Le Guide Culinaire (translated as The Complete Guide to the Art of Modern Cookery).

References[1] “The Carlton Hotel, Haymarket and Pall Mall, London,” Arthur Lloyd, http://www.arthurlloyd.co.uk/CarltonHotel.html[2] “Carlton Hotel, London,” Wikipedia, last modified August 29, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carlton_hotel,_London.[3] Auguste Escoffier, Le Guide Culinaire (Paris: Editions Flammarion, 1921), 309 (Truite saumonée), 530 (Selle d-agneau), 599 (Poussins), 614 (Vol-au-vent), 622 (Suprêmes de volaille Jeannette), 805 (Omelette surprise). Though I could not find the full title of “Truite Saumonée Lionienne” in Le Guide Culinaire, I did find a copy of a Carlton Restaurant “Lenten” dinner menu in The Epicure: A Journal of Taste, No. 173, Vol. XV from April 1908 (The Epicure, Volume 15, (London: 1908), 132).[4] “Suprêmes de volaille Jeannette,” Norsk rikskringkasting (NRK), https://www.nrk.no/mat/supremes-de-volaille-jeanette-1. 14070711.[5] Auguste Escoffier, A Guide to Modern Cookery, (London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1907), 59. [6] “Hutchinson Heinemann,” Penguin Random House, https://www.penguin.co.uk/company/publishers/cornerstone/hutchinson-heinemann.html[7] “César Ritz,” Wikipedia, last modified August 25, 2021, hittps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/César_Ritz.[8] “Auguste Escoffier,” Wikipedia, last modified August 17, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Auguste_Escoffier.[9] Escoffier, Le Guide Culinaire, 806.[10] Debra Kelly, “A Migrant Culture on Display: The French Migrant and French Gastronomy in London (Nineteenth to Twenty-First centuries),” Modern Languages Open, (2016), DOI: http://doi.org/10.3828/mlo.v0i0.148, 16.[11] Kelly, “A Migrant Culture on Display: The French Migrant and French Gastronomy in London (Nineteenth to Twenty-First centuries),”5.[12] Kelly, “A Migrant Culture on Display: The French Migrant and French Gastronomy in London (Nineteenth to Twenty-First centuries),”20.Katie Cape joined the Curatorial team in 2020 as an intern with the E.O. Hoppé Estate Collection, where she worked with the archive team to catalogue negatives and contact prints. Her experience in art database management was incredibly helpful as she aided in developing searchable records for the E.O. Hoppé Estate Collection housed at Curatorial Inc.