Artist Conversations | B.A. Van Sise Children of Grass

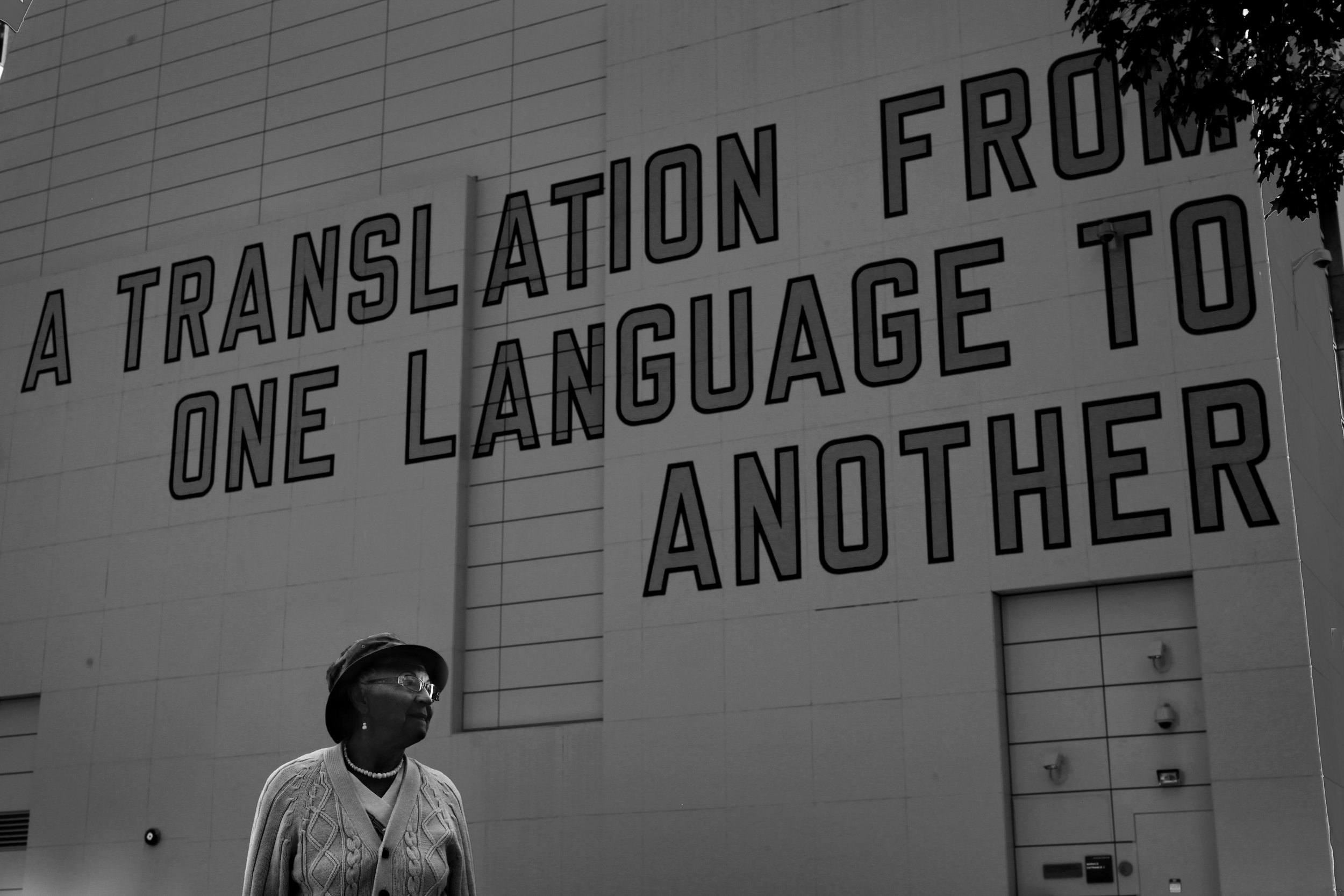

Displayed alongside the poems by new and well-known contemporary poets, B.A. Van Sise's Children of Grass presents an anthology of photographic portraits paying tribute to the poets of today.

On the occasion of announcing the traveling exhibition, Curatorial sat down with photographer and author B.A. Van Sise to discuss the inspiration behind the Children of Grass series, the experience of creating visual poems of contemporary poets, and how the two mediums, in particular, improve our understanding of what it means to be an American today.

The Children of Grass exhibition is now available for booking.

For exhibition details and booking information, visit our website.

Curatorial: Children of Grass certainly stands out as a more conceptual project of yours amongst your extensive photojournalistic career. What spurred the project and, further, when did your interest in poetry begin?

B.A.: My interest in poetry is much, much older; I was a voracious reader as a child and got very into it in high school. I was lucky in that I never had the dampening experience most folks have with it: here, kids, you are now forced and threatened to read volume after volume of dry poems about how great trees are. I started in my mid-teens, and everything I leapt into was alive: there was sex and death and gluttony and lust and feverous urgency, all the things that are engaging at that age and any other. I always stayed an absolutely insatiable consumer of poetry and in fact have been known to deluge friends, lovers, friends' lovers with unsolicited emails full of it from time to time.

I started this particular project because I got sick and had to have a surgery that knocked me pretty well out of commission in early 2016— had my abdomen cut open, was walking with a cane for a little bit. I'd been a travel photojournalist for years- so much for that, no hobbling across the continents for me- and decided I needed a project. I loved poetry, I reached out to a few poets whose work I admired and said hey I have this crazy idea and the first couple I pinged (Cornelius Eady, Gregory Pardlo [fig. 1], Dorianne Laux) got right back to me and said "cool cool, we're crazy too, let's do this." I thought I'd do maybe 10 or 15. It grew to about a hundred.

Curatorial: Many of the portraits in Children of Grass are highly composed with very strong symbolism. Were there any poetry techniques you saw filter through into your photography for this project?

B.A.: Poetry and photography are the same thing. They're, at their best, the same art form: the only two in which presence is required. Sculpture, theater, fiction, painting all come from the imagination. You can paint a scene without being there; you can write It without hanging out with homicidal sewer clowns. But to be a photographer you absolutely have to physically be present in your own life, the only clay you can sculpt with is the muck of reality. To be a poet you have to, in a similar sense, be absolutely present in your own life as well. You have to draw from experience.

But both are tinged with a certain dishonesty; there's no such thing as an honest photograph, any more than there's an honest poem: for the photographer, the "arbitrary" selection of moment, of light, of angle, of perspective make the record of a moment as much a product of the creator as of the millisecond they find and document. Similarly, if you put ten poets in front of the same scene, you'll get ten very different poems. We all view the world through our own lens.

I'm slightly fond of magic. I'm slightly fond of absurdity. That's definitely my own personal lens on the world, and in a very real way jumping out of journalism and into this was a step back into myself and my own reality. I worked, briefly, for Arnold Newman. I admired, terribly, Philippe Halsman. So I definitely brought the former's sense of visual structure and the latter's sense of playfulness to my work, while still making it about these things that I loved: these poems, these poets. So I'd work with the poets and say "here's what I want to do, what do you think?" and try to negotiate something that's about them, about their work, but also about, well, me and my love of the little bits of magic in life's little beauties.

Curatorial: The poems chosen to accompany the poets’ portraits range from prize-winning to most recently published. What was the process behind selecting which poems would be exhibited and how did the curation of poems influence the portraits you photographed, if at all?

B.A.: I didn't pick the poets, for the most part. I started with a list- people who'd been poet laureate, who'd won the Pulitzer, etc.- and from there I'd ask every poet to recommend two others I should feature and I'd reach out to them in a growing tree of outstretched branches. Once I was working with a poet, I'd go down to the Mid-Manhattan branch of the New York Public Library and take out every book they'd ever written, comb through it all, pick a couple poems that I thought would lend well to visual concepts that I'd sketch and create and then pitch to the poet. The choice of the notability of the poem was irrelevant- just kinda how it shook out. I imagine if you asked the poets they'd tell you the same thing most artists would: that what becomes popular is not often what the creator thinks is their best work.

I too Paumanok,

I too have bubbled up, floated the measureless float, and been

washed on your shores,

I too am but a trail of drift and debris,

I too leave little wrecks upon you, you fish-shaped island.

-Walt Whitman, AS I EBBED WITH THE OCEAN OF LIFE from Leaves of Grass

Curatorial: In Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, he posits nature as a shared experience and further asserts the importance of sharing individual greatness through artistic portals. In your opinion, how does this collaborative project between two different mediums improve our understanding of photography and poetry in the 21st century?

B.A.: All experiences are, at their root, shared experiences with different severity, at some level: everyone knows what it feels like to be in love, to be in lust, to hate, to need, to grieve, to be in pain, to be scared, to feel overlooked, to feel denied, et cetera. But as I mentioned before: I think poetry and photography are the same art form, just with different media. The core value of both is the instruction of empathy: this is my experience, and this is what I'm passing on from it. It's a way to try and see, literally or figuratively, through the lens of another, especially since so much of poetry, like photography, is tied up in personal interest and perspective. It's a product of the person, a product of the times.

The two art forms are also probably the most democratic media possible. They're defined by very low barriers to entry: anybody can make photographs, anybody can write poems. They're not necessarily good- five seconds on Instagram or on internet poetry blogs illustrates that well- but that's not necessarily important. Everybody has the chance to show others the world through their own lens.

It seems quaint to talk about it this way now, but the world felt like it was moving very, very fast when I started this project in mid-2016. I photographed Nikki Giovanni stepping through a giant torn American flag only two days after Donald Trump was elected president; Rita Dove met me for her portrait on the lawn at Monticello- at her suggestion, in an effort to make an image she felt was less loaded than what I'd suggested, if you can believe it- just a couple days later.

If you're talking about shared experience, I think it's necessary to view this project- and the people in it, both myself and the poets- through its time. It's not just a project of collaboration between a visual artist working with some literary artists to create images, but also a product of shared experience. We were absolutely, positively talking about the larger and increasingly emotionally engaging outside world as the project was ongoing. The early 2016 photographs and the late 2019 photographs definitely don't feel the same, because all of our shared experiences were changing so rapidly.

Curatorial: Is there a particular portrait or poem in Children of Grass that stands out to you personally?

B.A.: There's a lot of the poets in there, and a lot of the poems, but also a lot of myself; the poets were all selected from among themselves (I started with a group of notables and asked them to suggest other poets I should include, to avoid the tyranny of my own taste) but there are absolutely a lot of images and concepts that have aspects, people, experiences of my own. Poetry is generalistic in that way: a lot of people (myself included) often look at poems the way they hear music- oh this song is really relevant to my life. All that to say this: I have a lot of favorites; the two that stand out are not preferred because of the images but because of the experience- Dorianne Laux, whose portrait I don't favor- set the project in motion in a real way. She was the third or fourth poet I photographed and met me in an abandoned shack in the woods in North Carolina; she trusted that I wasn't a murderer and I trusted that she'd trust my vision (I was and am a fan of her work) and then she showed up with a pack of smokes and I think a flask and we just had a hoot and holler for a few hours beyond our fifteen minute shoot and it made me realize that I wanted to invest three years of my life into working with poets. The other is Jane Hirshfield- it's a fun image, but more importantly led to one of the more substantially constructive friendships I've ever had [fig. 3]. The falcon in her photograph is a stunt falcon. He appears on television and in commercials and is wildly expensive but also a true professional: before he was on Jane's head, he was on Game of Thrones. He had some absurdly majestic name but she and I kept calling him Larry. Anyway, Jane and I met for the first time that day (imagine having the fortitude to meet a total stranger and let him put a raptor on your noggin) and it began a now rather important friendship in my life: I visit her when I'm out in her neck of the woods, she visits with me when she's in mine. And, when I write things, do things, I show her first because I trust her to be honest. If you know anything about creating art, especially at a certain level- you know how much fragility and acceptance that requires.

Are there portraits I think are better than those two? Yeah, absolutely. Are there portraits that are closer to the core of the project, where I was more creative, more clever? Definitely. But life is larger. Life comes first.

A frequent contributor to the Village Voice and BuzzFeed, B.A. Van Sise is also one of the world’s busiest travel photographers. His work as both a photographer and author has previously appeared in the Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, the Daily Mirror of London, and approximately 250 other publications, in addition to exhibitions at the Peabody Essex Museum, the Museum of Jewish Heritage, Center for Creative Photography, and the Whitney Museum of American Art. He is a graduate of the prestigious Eddie Adams Workshop and a National Press Photographer’s Association award-winner. A number of his portraits from the Children of Grass project are in the permanent collection of the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian.